Forest environments vary widely in their capacity to attract and sustain wildlife. From the dry scrub forests of the north-west to the moist lowland forests in the south-east, Trinidad can boast of a wide range of these forest communities and, by extension, an impressive menagerie of wildlife. Cat’s Hill offers two very distinct forest types. On one hand there exists a sizeable expanse of seasonal forest, an extension of the Victoria Mayaro Reserve. In comparison, a large teak plantation has been carved out of the forest which is maintained and logged for timber. So how do wildlife communities differ between the forest types?

The Cat’s Hill teak plantations were established under the Taungya system in the 1970’s and 1980’s which effected the gradual conversion of native forest into teak. Once established, the teak plantations were probably managed under a modified version of the Periodic Block System (PBS). The PBS involves the felling of trees within demarcated blocks after which the block is closed and left to regenerate before cutting can resume. According to Sustainable forestry in Trinidad (Fairhead and Leach 2001) “In the early 1970s, the PBS was further adapted to incorporate ‘silvicultural marking’. In this, in theory ‘stems are selected for sale by a team of highly skilled markers who go through the block systematically and physically mark trees that should be removed. In principle, the trees that are marked are those which in the next 30 years would not do as well as others that they are shading, or competing with. They may either be mature, or faulty or likely to become so. The trees in one block are sold to woodworkers over a 2 year period, after which the block is closed from sales and allowed to regenerate for the cutting cycle of 30 years’ (Clubbe and Jhilmit 1992:5)”. As a result, the entire plantation consists of different coupes of varying ages.

A key feature of a teak plantation is its understorey. Teak trees shed their leaves during the dry season, allowing light to penetrate. Even with their leaves, teak trees tend to be spaced far enough that sufficient sunlight is able to reach the forest floor year round. As a result, plant growth is rapid and the understory can become very dense if left unchecked. Various plants quickly become established but in many areas of Cats Hill the dominant feature in many coupes is the introduced Kudzu vine (Pueraria lobata).

These dense growths and vines, as well as the copious volume of leaves shed by the trees, can seriously encumber woodcutters. As a result, actively managed teak plantations are usually cleared by a controlled burn on a yearly basis. The accumulated vegetation ensures that the fires are well fuelled, resulting in a clean burn (and also deals with any critters the woodcutters rather not encounter). Teak trees themselves are fire resistant thanks to the high silica content of their trunks. They are not, however, fire-proof. As noted in Sustainable forestry in Trinidad “Teak has proved perpetually vulnerable to fire; plantations are routinely devastated by burning, especially in those years of unusually serious fire which occur unpredictably yet frequently in Trinidad’s climate. Such is the frequency with which teak plantations burn that a public perception has arisen that teak actually needs fire for successful growth, and that these fires are set by foresters as part of plantation management strategy (Trinidad and Tobago Forester, 196x)”. The only other plant that routinely survives the burn is the ubiquitous Gru-Gru Palm (Bactris major). This fire control allows some teak coupes to be quite clean, as compared to the leafy tangle of fire free areas.

Teak plantations, like many monocultures, typically do not support a diverse range of plant and animal species. The extensive teak fields of Quinam, for instance, can be quite uninteresting for a naturalist. The frequent fires strip the plantations of competing plant species and other terrestrial wildlife. Turning once again to Sustainable forestry in Trinidad, it is noted that “monoculture plantations are strongly critiqued by other interest groups within Trinidad who give priority to biodiversity and wildlife conservation. In the south-east they have, for example, been strongly criticised by the South-East Hunters’ Association, as ‘creating animal deserts in the interests of commercialisation’ (Interview, Mohan Bholasingh, 30 June 1999). Indeed the Association was started in 1994 in response to the sense that forestry in Trinidad was too geared towards commercial production, not wildlife, and to lobby government and educate the public on the problems of monoculture plantations”.

Thankfully, the Cat’s Hill teak plantation is a bit different. Firstly, the teak fields are surrounded by dense natural forests and in many areas the teak fields are actually quite narrow so that natural forest is never that far away. Secondly, the Cat’s Hill teak field is not a pure teak stand. Several native tree species have managed to grow within the teak fields and include useful fruiting trees such as Hogplum (Spondias mombin) and Juniper (Genipa americanna), providing refuge and food for wildlife. The proximity of natural forests also acts as a “seed bank”, allowing fire cleared coupes to be quickly re-vegetated soon after the passage of a fire. So what type of wildlife survives in this environment?

In terms of the area’s fauna, birds are perhaps the most obvious and the variety of birds inhabiting the forest is quite surprising. The forest edge is home to large numbers of seed eating Sooty and Blue-backed Grassquits which feed on the grassy verge maintained by the energy companies operating in the area. Also common are the insect eaters like the gorgeous Rufous-tailed Jacamars, Tropical Peewee and several other flycatchers which hunt for their prey from low branches.

I have often heard the calls of Little Tinamou from within the teak. Even Gray-necked Wood Rails are present near several decent sized streams that drain the field, providing the wetter environments that these birds favour.

Surprisingly, many fruit eating birds can be found in the teak coupes. Purple and Red-legged Honey Creepers, Green-backed Trogons and White-bearded Manakins can be seen. The teak trees themselves produce no fruit and these birds probably feed on the fruits produced by the parasitic bird vine (Phthirusa sp.) which grows on the branches of the teak trees. Additionally, the fruit eaters probably take advantage of the occasional native fruit trees mentioned earlier.

Teak itself produces large seeds. However, the only birds capable of eating these seeds are probably the parrots and the common Orange winged Parrots are a regular sight. I have never seen Blue-headed Parrots in the area but I have seen their smaller relatives, the Lilac-tailed Parrotlet. The smaller Parrotlets feed on the fruit sources already mentioned.

The teak fields are also very good for finding raptors. The bare ground, which exists in many of the coupes, offers clear hunting ground for ambush predators like Gray Hawks, White Hawks and Grey-headed Kites. The openness of the teak upper-story must also make maneuvering easier for these broad winged raptors.

Rarer raptors are also encountered here including Hook-billed Kites (Chondrohierax uncinatus). Hook-billed Kites are awkward looking birds when perched. Their short legs seem to be positioned unusually far back along their bodies. They feed largely on land snails for which they possess a specialized, curved bill which facilitates the extraction of the snail from its shell. Another rare raptor which can be seen here is the magnificent Black-Hawk Eagle.

The commonest raptor here is the Plumbeous Kite (Ictinia plumbea). Some of these insect eating birds are resident year round in Trinidad, but the local population is augmented by migrants from South America between the months of March and October. During this time, these kites are everywhere in south Trinidad and the Cat’s Hill teak plantation gets more than its fair share. Always perched on exposed branches (look out for wing tips that project beyond the tail for quick identification), they are the easiest raptor to see here.

But what about other animals that aren’t as easy to see as birds? There are mammals that live in the teak. The Red-tailed Squirrel (Sciurus granatensis) is relatively common (a food source for the hawks!). A few bat species also live here. One interesting species is this CommonTent Bat (Uroderma bilobatum), at home under its “tent”. Amazingly, these bats will chew the mid rib of certain broad leaves in order to make the ends droop, thereby creating a tent shelter where they are protected from the elements and those hungry hawks.

To get an idea of the other mammal species in the area I set up the trail camera on the bank of one of the streams mentioned earlier. The spot was adequately baited with a range of food items and the camera was left for 15 days.

I fully expect small populations of Agouti to live in the teak fields. I assume they will feed on teak seeds when available but there should be enough alternative food sources. The Kudzu vines that grow here might be a food item. The vines are an excellent fodder – according to the research, the crude protein content of kudzu can be as high as 18.45% in leaves (falling to 7.42% in stem sections). The seeds are not edible. In addition to the Kudzu, the ubiquitous Gru Gru Palms produce large seeds that would be acceptable food for an Agouti. Other than Agouti, small mammals such as the Robinson’s Opossum and small rodents probably eke out a living.

The trail camera, however, seems intent to prove me wrong.

Quite disappointing. We moved the camera to another position deeper in the teak field (but still close to a waterway) and baited it with hogplums.

It would seem that the terrestrial fauna of the teak plantation is poorer than I thought. We even checked the soft mud at the water’s edge at several crossing points for animal tracks and still could not find evidence of mammals. While I can accede to the absence of larger animals, such as Agouti, I find it hard to believe there are no small rodents. Are the harsh conditions too much for even a forest rat? Perhaps later visits will prove otherwise.

With the frequent fires, the terrestrial reptile and amphibian life is probably very poor as well but I have seen a few dead snakes on the road (victims of the oilfield workers whom, for some reason, traverse these bumpy, potholed roads at breakneck speeds, unconcerned about the damage to their company vehicles). Most have been carcasses of the common Cat-eyed Snake (Leptodeira annulata ashmeadi). Other than that, I was surprised to encounter this curious beast one morning in 2009.

Often mistaken for a snake, the so called “two-headed snake” is actually a legless lizard. The White Worm Lizard, (Amphisbaena alba) is said to be widely distributed in Trinidad and Tobago. While harmless, they do have quite a temper and will lash out if harassed. They are sometimes found in the subterranean nests of leaf-cutter ants (aka Bachac) and this probably saves them from the ravages of the fires.

I expect the insect diversity to be affected as well. While I can’t comment on any other insect families, the teak field is relatively poor when it comes to butterflies. This is directly related to the poor variety of plant species – a limited variety of plant species means a limited range of potential foot plants for caterpillars to feed upon. That said, several species, including Tithorea harmonia, Ithomia agnosia pellucida, as well as various Satyridae and Hesperiidae, can be found in the better vegetated coupes.

There are several interesting epiphytes which grow on the teak trees. Several orchid species can be found including Campylocentrum pachyrrhizum, Ornithocephalus gladiatus and Maxillaria camaridii. Bromeliads are present as well including the interesting Werauhia gigantea (formerly Vriesea amazonica).

Beyond the teak lies the “real” forests of the Cat’s Hill Reserve – a mixture of flat and hilly land. Along the road the forest has been disturbed by the actions of oil extraction companies. The presence of oil in these forests is probably the only reason squatting settlements and small scale “slash and burn” agricultural plots have not become established in Cat’s Hill. The oil extraction activity is not without its negative side effects – small oil spills do occur and clearings have to be made to facilitate oil wells and related equipment. However, the more serious effect has to be the creation of access roads through the reserve. The roads themselves are quite useful for oilfield works and naturalists alike, however, they open up Cat’s Hill to that other forest activity – hunting.

Several hunting camps have carved out small clearings along the road in the forest. Because Cat’s Hill is a state forest reserve, hunting is permissible during the open season. A few hunting camps have also been constructed in the teak fields (where hunters would be in a more hospitable environment and yet reasonably close to the forests). The camps in Cat’s Hill are much simpler than some of the advanced structures that can be found in Edward’s Trace, but I wonder if it is allowed to continue whether the same would occur here as well.

It begs the question of what the effect of hunting in Cat’s Hill has been. Extensive wildlife studies appear to be lacking in Trinidad and Tobago and these are sorely needed if the government is to properly reformulate our existing conservation laws. I have noted the apparent scarcity of Agouti in Cat’s Hill, a species which is also the main target of the hunters that frequent the area. Surely this is not a coincidence.

Besides wild game animals, Cat’s Hill is full of other interesting wildlife. Birds are plentiful but they are harder to see here in the dense foliage than out in the bare teak fields.

Earlier in August, I was quite surprised to hear a Black-faced Ant-thrush (Formicarius analis) calling from the forest along the road. This, like the Gray-throated Leaftosser I mentioned in May’s report, is a species usually associated with the higher altitude forests. Is it possible that other “north only” species such as Scaled Antpitta also reside in south Trinidad?

A wide variety of butterflies and moths can be found in the Reserve but they tend to be widely distributed. The roadside growths of Railway Daisy (Bidens pilosa) are always worth checking along with the occasional clumps of Black Sage (Cordia curassivica). In the dry season, puddles of water on the roadway also attract several mineral seeking species.

Other than birds and butterflies, more insidious animals fly through these forests. The blood stains on the neck of this cow, which we once found grazing at the forest edge, indicate that vampire bats inhabit the area. Vampire bats were identified as the culprit behind the 1925 outbreak of rabies in Trinidad, spreading the virus via their saliva. I have been assured that rabies no longer poses a threat to human life in Trinidad.

As for reptiles, I know that Fer-de-Lance are present from the occasional dead specimen killed on the roadway. Once I came across this Dos Cocorite (Pseustes poecilonotus polylepis) sunning itself on a leaf along the road. The Spiny Tree Lizard (Plica plica) and Tegu (Tupinambis teguixin) are also common.

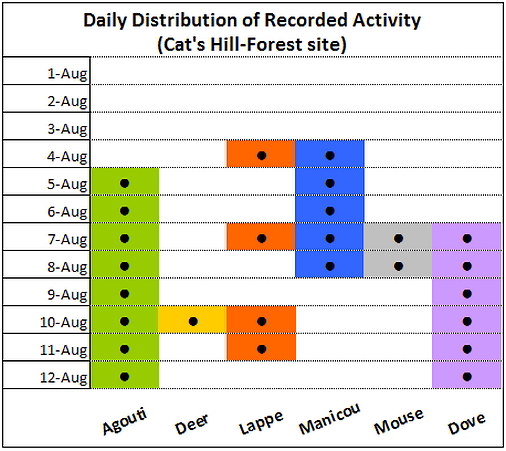

Earlier this month, my father and I were driving along Cat’s Hill when we noticed a large flock of Orange-winged Parrots feeding in a large fruiting forest tree. As we were looking for a site to place the field camera we decide to investigate as fallen fruit is likely to attract a lot of wildlife (coincidentally, this was also roughly the same spot that I had previously heard a Grey-throated Leaftosser). Apparently there were a good number of both Orange-winged and Blue-headed Parrots feeding in the tree that morning – as we approached, the combined racket they made was fantastic. The birds had led us to a really nice spot where the ground was covered with fallen half chewed Pois Doux beanpods (wiser folk later narrowed down the identification for me to a probable Inga laurina). So we set up the camera and left.

Twelve days later we retrieved the camera. In my experience, the average haul for such a period is about 30 images in a decent location. Of this, half are likely to be blanks. But this was evidently quite a busy spot – the camera had recorded 161 images. We were too excited to wait until we got home to review the images so we plugged the memory card into a camera.

My Dad began to get concerned that this Manicou might have accounted for all the photographs. I was beginning to think he was right. But then this came up.

My jaw dropped. Here was an animal I have always hoped to find. The Lappe (Agouti paca) is a large rodent and close relative of the familiar Agouti. We were surprised as we always associated Lappe with waterways. Perhaps there was a stream nearby? The animal is a good swimmer and is reputed to always dig a secondary escape tunnel in its underground den that exits underwater. More surprising images were to come.

An Agouti (Dasyprocta leporina). These rodents have been identified as important distributers of seeds in the forest, sometimes taking seeds and burying them far away from the parent tree. Forgotten seeds then germinate. More recent studies suggest that sometimes, after one agouti has buried a seed somewhere near the edge of its territory, a rival Agouti will then steal and re-burry it even further away from the parent tree.

Rats! These small forest rodents are probably not identifiable from these pictures. I suppose they fulfill the same function that other rodents do – feeding on the small bits and pieces of whatever edible items they find and aiding in seed dispersal. They in turn are no doubt food for owls, ocelots and snakes alike.

The Gray-fronted Dove (Leptotila rufaxilla) was a very frequent visitor to this spot. Evidently the Pois Doux seeds are quite attractive to them as a food source. Differentiated from the White-tipped Dove by the bare red skin around its eye, I did not realize just how common they were in forests, evidently outnumbering the number of White-tipped Doves that are present. Photographs of Grey-fronted Doves represented the majority of images captured by the camera during this period.

From the most common we go to the scarcest. More surprising than the Lappe, it is fitting that the most impressive recording of the set be left for last.

This Red Brocket Deer (Mazama americana) appeared in two consecutive images during the final days that the camera was in place. The only time I have seen Red-brocket Deer in the wild was when one sprinted across the road in Cat’s Hill (with the sound of hunting dogs somewhere close behind).

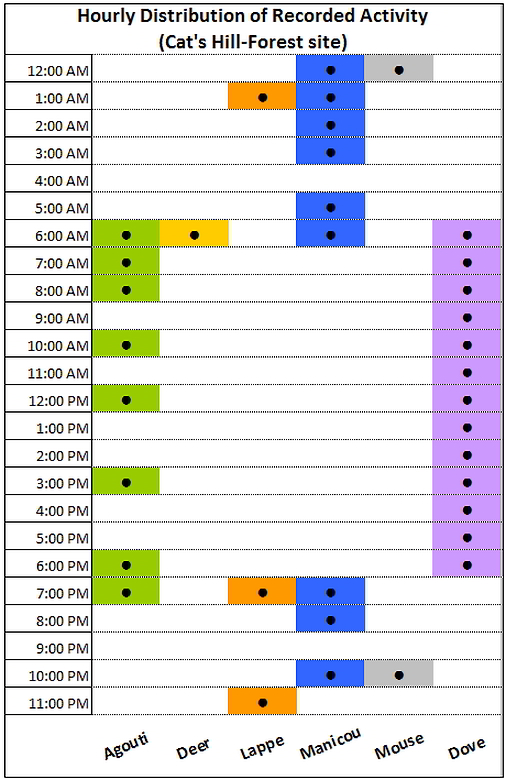

A lot of useful information can be determined from these images. By noting the times, you can get a pretty good idea of when these animals are active.

Lappes are clearly nocturnal, appearing between the hours of 7:00 pm and 1:00 am. There were actually two Lappes involved. The coat spotting differs between the two animals. These were apparently a male and female pair as you can just make out male genitalia on one animal and what would appear to be mammary glands on the other. Interestingly they always appeared at the far end if the image and never seemed to stop to fed. I suspect this pair may have a den in a nearby hollow and happened to frequent the area as a path to somewhere else.

Agoutis were strictly diurnal. No surprise there. It is hard to tell the individuals apart but size differences suggest that at least two individuals were involved.

Not much can be determined from the sole Red Brocket Deer. It appeared at dawn but from what I have read they are nocturnal. Numerous welts can be seen on its body. This is likely to be a mite, similar to or perhaps the same as the obnoxious bête rouge.

What is interesting is the absence of Robinson’s Mouse Opossum (Marmosa robinsoni). This is a very common animal in densely vegetated areas and frequently turns up in other locations. I suspect the relative openness of the forest floor deters this small opossum – it is probably hesitant to cross large open spaces, preferring to stick to vine tangles and low bushes.

It also has me wondering how important parrots and other messy eaters, such as monkeys, are in the forest food cycle. They must drop and dislodge significantly more fruit than would have fallen naturally to the forest floor, which in turns feeds the ground dwelling fauna.

Outside of the trail camera recordings, I have seen Red Howler Monkeys, Ocelot and Tyra in Cat’s Hill. Additionally, we occasionally detect the smell of Porcupine. Neotropical River Otters probably live here also given the proximity to Inniss Field (see Known Unknowns). I have never seen any sign of Quenk (Tayassu tajacu).

So what does this all mean? The site of the second trail camera was probably no more than 50 feet from the roadway (close enough to hear passing cars). Hunters are active here as evidenced by a rusty shotgun shell near the camera from some hunting season past. I would have expected that hunting pressure would have restricted such rarely seen animals to the deeper parts of the forest. Yet there they are. Could it be that the effect of hunting has not been that severe? In terms of the teak plantations I am curious about what other animals live in the fields. But for now it’s time to hold back a bit on further investigations. Hunting season is upon us and it is not wise to leave the trail camera out there or wander about in forests. Hopefully we shall continue the story of Cat’s Hill next year.