“We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know”- Donald Rumsfeld

There are a lot of natural and modified environments in Trinidad and Tobago and observing wildlife in these areas can be very difficult as anyone who spends time in our forests, savannahs and swamps will know. It stands to reason, therefore, that there are a lot of gaps in our knowledge of the flora and fauna that reside in these areas.

Consider this hypothetical example of a butterfly in the forest canopy. Butterflies can be tough enough to observe at ground level so new or rare species turn up only every now and then. But imagine a species which is restricted entirely to a life in the high forest canopy. It is unlikely that a casual collector would chance upon that species. To further complicate the matter, what if it only resides in the canopy of forests in a difficult area such as the highest peaks of the Trinity Hills, and then too is only active at dusk? We may never know about the existence of this butterfly, much less learn about its life history.

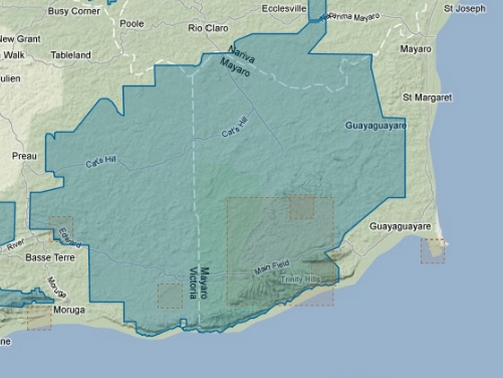

But even in reasonable conditions there are interesting things that escape our attention. Take the Victoria-Mayaro Reserve for example. Vast forests carpet the region and while some of this is disrupted by oil extraction, the area still contains an abundance of plant and animal life. I visit as often as I can and unexpected things do turn up from time to time.

Sometimes finding things just requires a healthy dose of luck. What do I mean by luck? Imagine parking your vehicle along the forest road, stepping out the door and having this fly past you and land on a nearby shrub.

It may not look significant but it is. This is Synpalmides phalaris. It’s a member of the Castniidae family, part of the Lepidoptera – the same group to which butterflies and moths belong. Of the twelve Castniidae species known in Trinidad, only one is common and a quick check with the relevant experts revealed that this particular species has only been documented twice before in Trinidad. Who knows how many people have encountered S. phalaris without realizing what it was.

You also have to depend on all your senses – especially your hearing. Of course Lepidoptera don’t vocalize but birds do. Recently while driving through these forests I heard the unmistakable sound of a Gray-throated Leaftosser (Sclerurus albigularis) calling from the undergrowth.

I say ‘unmistakable’ but I should qualify this by saying that it is unmistakable once you get familiar with the call. I myself only recently cemented it into memory which is probably why I never noticed it in Cat’s Hill before. Leaftossers are usually regarded as residents of the higher elevation forests and yet here it was among the oil derricks characteristic of the deep South. Is it resident here? Or is there something else going on? Is there some local dispersal from the higher elevations of the Trinity Hills to the surrounding lowlands during the dry season (consider the Ornate Hawk Eagle of April 2010)?

Another surprise for me was finding a Great Antshrike in the forest understory. I never saw this species anywhere in South Trinidad although I half expected that it should be here (indeed, at least one fellow birdwatcher has reported it from the South-West). Similarly, I have never seen a Trinidad Motmot in the Victoria-Mayaro area but others have. It just goes to show just how much observation time is needed for anyone to really understand the biodiversity of an area.

But it’s not only the unusual birds that are likely to go unnoticed in these forests. Sometimes ordinary birds are just as hard to find. Throughout most of Trinidad’s forests lives a small terrestrial bird called the Little Tinamou (Crypturellus soui). I have had the good fortune to see several rare bird species in Trinidad but I have never yet seen this secretive yet relatively common species myself. Thankfully, for the last six weeks I had another pair of eyes in the forest.

For three weeks the trail camera had been patiently monitoring a Leafcutter Ant trail in the Inniss Field as I was curious whether or not forest mammals would use the paths created by the ants (Incidentally it appears they do not). During this time it twice detected Little Tinamou.

Better known to country folk as “Caille”, the Tinamou was believed to utter its haunting melancholy call every fifteen minutes (which isn’t true). It is hunted but I suspect such a small game animal is not usually worth the effort. Most encounters probably occur when the bird is accidentally flushed from the forest floor and it flies off a short distance. Interestingly they do not possess a functional rear toe which renders them unable to perch and restricts them to life on the ground.

In addition to the three weeks of ‘Bachac’ trail duty, the camera was also setup on the banks of a decent sized stream in the Inniss Field for one week.

The site was promising and I would have loved to leave it for longer but the threat of rising water levels from the unexpected rainfall in April and concerns over its exposed position, which increased the chances of theft, led me to move it prematurely. For the time that it was there it did manage to detect this rarely seen animal.

Neotropical River Otters (Lontra longicaudis) are known to inhabit the larger southern drainages in Trinidad but I was surprised to have one so far inland. They are said to be diurnal and the timestamp on the photographs confirmed this. A quick search in the watercourse turned up a few Brown Coscarob and Bronze Corydoras catfish on which the Otter might feed but it probably has to patrol a large stretch of watercourse in order to get enough food. I have read that they also consume a lot of insects. The presence of the otter here might indicate they also inhabit the Inniss-Trinity Reservoir.

Also of interest, as my father pointed out, was what the camera did not detect. Together with my previous camera, I estimate the cameras have logged a total of 57 days (1,368 hours!) in Cat’s Hill and Inniss Field. In all that time they have never photographed a single Agouti (Dasyprocta leporina). I’m sure they are present but when I consider how relatively easily the cameras detected Agouti in other forests (such as in Quinam) I can’t help but wonder if it might indicate that hunting pressure on Agouti is heavy in the area. While I also cannot rule out the possibility that it might be the result of inappropriate camera placement, this speculation of overhunting jibes with the conclusions of at least one wildlife survey (Nelson 1996) which suggests that Agouti populations in the nearby Trinity Hills Wildlife Sanctuary are significantly lower than that of other benchmark areas.

This brings us to another mammal species that is present in the Moruga area. Specifically, I refer to the two footed kind. It should surprise no one that poachers and marijuana farmers are active here. Perhaps indicative of this human activity was this dog that crossed the camera’s path back at the ant trail.

It doesn’t look like a hunting beagle so I can only guess who this belongs to. Farmer? Trap gun poacher? Subsistence hunter?

I wonder if the southern lowland forests can support these activities? Unfortunately, the lack of data complicates the issue of wildlife conservation in Trinidad and Tobago. The South-Eastern Hunters Association has put forward an alternative position on wildlife populations which supports their view that legitimate hunting is sustainable. Their position (as briefly outlined in Science, policy and national parks in Trinidad and Tobago (Leach & Fairhead 2001) is/was based on the assumption that “The diameter of the circle in which an animal runs when chased by hunting dogs can be used as a gauge of its territory and hence population levels; a smaller circle suggesting smaller territory and higher population. The correlation between running area and population varies not only by species but also by terrain and other factors”. A very interesting theory and one which draws attention, as Leach and Fairchild pointed out, to variations in the capacity of the immediate area to support wildlife. But is it based on an accurate assumption? In any event, while I am in support of many of the efforts of the SEHA, it might be impractical to implement such a resource intensive survey method on national scale.

All of this should serve to highlight that we are not exactly sure of what is happening in South Trinidad and elsewhere. What exactly is the status of our wildlife? With respect to our birdlife I would not be too surprised if one day Stripe-breasted Spinetail and Collared Trogon are found in the Victoria-Mayaro lowlands. But I imagine the real revelations are to be made on the heights of the Trinity Hills. Possibly the last refuge for whatever remains of the southern population of Trinidad Piping Guans, perhaps the more inaccessible slopes might also be home to Black-faced Antthrush, Scaled Antpitta and transitory Swallow-Tanagers. Who knows what else is up there?