While I have been experimenting with camera traps in south Trinidad for several years now, my methods were relatively haphazard – the strategy was more or less just to drive about and pick some patch of forest that looked interesting.

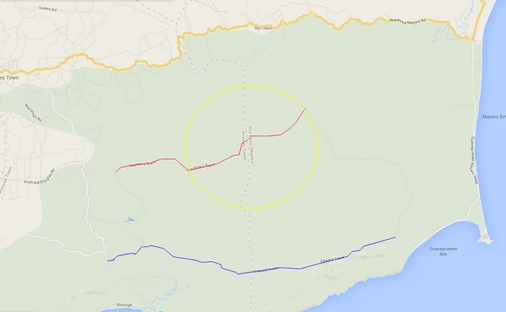

The positive results of 2012’s trap sessions in the Victoria Mayaro Reserve encouraged me to pursue a more rigorous ‘survey’ and so, in the closed season of 2013, my dad and I attempted a structured camera trapping session in Cat’s Hill with one objective in mind – to get a feel for the status of the ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) in the area.

However, after the 2013 sessions were completed, the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources suddenly announced the imposition of a two year moratorium on hunting beginning with the 2013/14 season.

As galling as this was to the hunting fraternity, this provided a unique opportunity as we could look at the camera captures both before and during the moratorium and possibly be able to see if there was any change in wildlife numbers – not just of ocelot, but of all animals.

So it was back to Cat’s Hill in 2014 and, after several months, this session is now complete. In brief, for both 2013 and 2014, cameras were placed at set intervals along the road, approximately 50 feet into the forest. The cameras were then left for a three week period. A total of six sites were surveyed in this manner and the results have been remarkable.

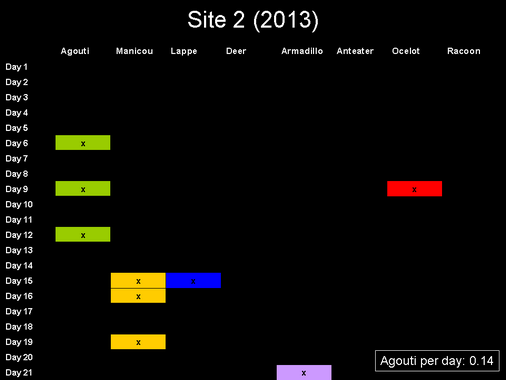

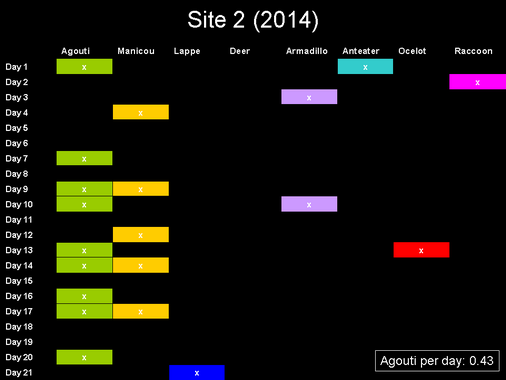

As a way of comparing the two years I looked at the percentage of days that animals were recorded, so that if an animal turned up on 7 of the 21 days it would have a 33% detection rate. Between 2013 and 2014 the detection rates for agouti certainly increased. In site #2, for example, the detection rate for agouti increased from 14% in 2013 to 43% in 2014 (I called it “Agouti per day” in the slides but “detection rate” is a more appropriate term).

And yes, ocelots were found. It is encouraging to see them not only here but in the trail camera surveys conducted by others around the country.

These observations, and observations by other camera trappers, support the general consensus that ocelots are primarily nocturnal animals, only occasionally becoming active during the day. The timing of the photos, by extension, support another view – that is because agouti are diurnal and ocelot are mainly nocturnal, the ocelot cannot be a major predator of agouti. Given the numerous black-eared opossum photographs that the camera recorded at night, I suspect that manicou are a major prey item for these cats (it seems that manicou spend a lot of time on the forest floor foraging).

The other key observations are not unexpected. The agouti is the most widely hunted game species in Trinidad and Tobago so it only makes sense that, once the season was closed, the population would rebound (remember that agouti are likely to have multiple litters per year). In a 21 day period, the number of days in which agouti were recorded increased at all survey sites.

It is also notable that, for the first time in Cat’s Hill, I saw a pair of agouti feeding comfortably out in the open this year. This behavior is seen in other areas of the country areas where agouti are not persecuted, so the observed behavior might be a response to the lack of hunting during the last 12 months. It would be interesting to hear what the hunters in the area make of the agouti population when the season reopens.

New in 2014 for me was the crab-eating raccoon (Procyon cancrivorus) which I had been hoping to see for quite some time.

So the fact that wildlife has responded positively to the moratorium is not what needs to be questioned (nor should it be a surprise). Rather, we need to know what is the carrying capacity of our forests and what the sustainable rate of extraction is. How much can we hunt and still maintain a viable population?

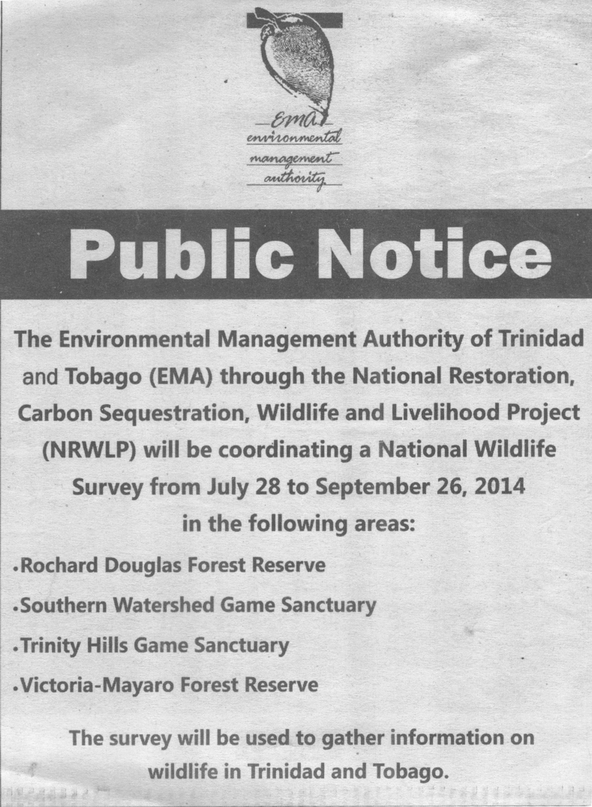

With these questions in mind, I was somewhat pleased to find out that the long awaited wildlife survey has started. I say ‘somewhat’ because the methodology has not yet been disclosed to the public, so that I am not certain what is being proposed.

The surveys are being conducted by the EMA in conjunction with the Forestry Division and the appropriate hunting associations for the area. This first survey will run from 28th July to 26th September.The authorities might be waiting for the completion of the survey to issue a full report but this will rule out any chance of comment by stakeholders. The present survey (to be conducted every year for the next three years) seems to be based on straight line transects during the day which means it is limited to certain species – i.e. this survey would be largely limited to agouti (which I suppose is a good first step as this is the most popular game species).

Nonetheless, I sincerely hope the scope of the survey is expanded soon. While I don’t believe there is a threat to common species like the agouti, I do have concerns about the populations of quenk/wild hog (Tayassu tajacu) as in the three years of trapping in Cat’s Hill, I have failed to photograph a single one.

In addition to the wildlife survey, the government has also drafted the Forestry, Protected Areas and Wildlife Conservation Bill with a view to replacing the ancient Conservation of Wildlife Act (and other Acts) with more appropriate legislation. The draft policy was made available for public comment and is now in the process of being finalized.

In line with these developments, there are some serious questions to be answered. Given that hunting has taken place for many years and we still have our wild game animals it would seem that the rate of extraction was not excessive 20 year ago. But does the same still apply today? What has been the impact of the wild meat fetes at Carnival and Christmas? Can our forest meet this supply? How much of the meat at these events originate from Trinidad and how much comes from other countries? Or has hunting pressure actually fallen? Is hunting as popular as it used to be? The government is heading in the direction of wildlife farming but can we be sure that the system will be sufficiently supervised so that wild caught meat is not ‘laundered’ in the wildlife farming system?

Unfortunately I have no answers for these questions. Perhaps by the time the surveys are concluded and the new forest policy is implemented the situation will be clearer. Perhaps.